In this post, we’d discuss the “intelligence explosion” in detail. Let’s start by defining it. According to techopedia (https://www.techopedia.com):

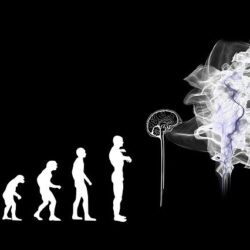

“Intelligence explosion” is a term coined for describing the eventual results of work on general artificial intelligence, which theorizes that this work will lead to a singularity in artificial intelligence where an “artificial superintelligence” surpasses the capabilities of human cognition. In an intelligence explosion, there is the implication that self-replicating aspects of artificial intelligence will in some way take over decision-making from human handlers. The intelligence explosion concept is being applied to future scenarios in many ways.

With this definition in mind, what kind of capabilities will a computer have when its intelligence approaches ten to a hundred times that of the first singularity computer? Viewed in this light, the intelligence explosion could be more disruptive to humanity than a nuclear chain reaction of the atmosphere. Anna Salamon, a research fellow at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, presented an interesting paper at the 2009 Singularity Summit titled “Shaping the Intelligence Explosion.” She reached four conclusions:

- Intelligence can radically transform the world.

- An intelligence explosion may be sudden.

- An uncontrolled intelligence explosion would kill us and destroy practically everything we care about.

- A controlled intelligence explosion could save us. It’s difficult, but it’s worth the effort.

This brings us to a tipping point: Post singularity computers may seek “machine rights” that equate to human rights.

This would suggest that post-singularity computers are self-aware and view themselves as a unique species entitled to rights. As humans, the U.S. Bill of Rights recognizes we have the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If we allow “machine rights” that equate to human rights, the post-singularity computers would be free to pursue the intelligence explosion. Each generation of computers would be free to build the next generation. If an intelligence explosion starts without control, I agree with Anna Salamon’s statement, it “would kill us and destroy practically everything we care about.” In my view, we should recognize post-singularity computers as a new and potentially dangerous lifeform.

What kind of controls do we need? Controls expressed in software alone will not be sufficient. The U.S. Congress, individual states, and municipalities have all passed countless laws to govern human affairs. Yet, numerous people break them routinely. Countries enter into treaties with other countries. Yet, countries violate treaties routinely. Why would laws expressed in software for post-singularity computers work any better than laws passed for humans? The inescapable conclusion is they would not work. We must express the laws in hardware, and there must be a failsafe way to shut down a post-singularity computer. In my book, The Artificial Intelligence Revolution (2014), I termed the hardware that embodies Asimov-type laws as “Asimov Chips.”

What kind of rights should we grant post-singularity computers? I suggest we grant them the same rights we afford animals. Treat them as a lifeform, afford them dignity and respect, but control them as we do any potentially dangerous lifeform. I recognize the issue is extremely complicated. We will want post-singularity computers to benefit humanity. We need to learn to use them, but at the same time protect ourselves from them. I recognize it is a monumental task, but as Anna Salamon stated, “A controlled intelligence explosion could save us. It’s difficult, but it’s worth the effort.”