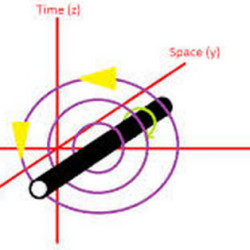

The Tipler cylinder is a cylinder of dense matter and infinite length. Historically, Dutch mathematician Willem Jacob van Stockum (1910–1944) found Tipler cylinder solutions to Einstein’s equations of general relativity in 1924. Hungarian mathematician/physicist Cornel Lanczos (1893–1974) found similar Tipler cylinder solutions in 1936. Unfortunately, neither Stockum nor Lanczos made any observations that their solutions implied closed timelike curves (i.e., time travel to the past).

In 1974, American mathematical physicist/cosmologist Frank Tipler’s analysis of the above solutions uncovered that a massive cylinder of infinite length spinning at high speed around its long axis could enable time travel. Essentially, if you walk around the cylinder in a spiral path in one direction, you can move back in time, and if you walk in the opposite direction, you can move forward in time. This solution to Einstein’s equations of general relativity is known as the Tipler cylinder. The Tipler cylinder is not a practical time machine, since it needs to be infinitely long. Tipler suggests that a finite cylinder may accomplish the same effect if its speed of rotation increases significantly. However, the practicality of building a Tipler cylinder was discredited by Stephen Hawking, who provided a mathematical proof that according to general relativity it is impossible to build a time machine in any finite region that contains no exotic matter with negative energy. The Tipler cylinder does not involve any negative energy. Tipler’s original solution involved a cylinder of infinite length, which is easier to analyze mathematically, and although Tipler suggested that a finite cylinder might produce closed timelike curves if the rotation rate were fast enough, Hawking’s proof appears to rule this out. According to Hawking, “it can’t be done with positive energy density everywhere! I can prove that to build a finite time machine, you need negative energy.”

One caveat, Hawking’s proof appears in his 1992 paper on the “chronology protection conjecture,” which has come under serious criticism by numerous physicists. Their main objection to the Hawking’s conjecture is that he did not employ quantum gravity to make his case. On the other hand, Hawking and others have not been able to develop a widely accepted theory of quantum gravity. Hawking did just about the only thing he could do under the circumstances. He used Einstein’s formulation of gravity as found in the general theory of relativity. Another fact, Hawking’s proof regarding the Tipler cylinder is somewhat divorced from the main aspects of his paper and could be viewed to stand on its own. However, in science we are always judged by the weakest link in our theory. Thus, with a broad brush, the chronology protection conjecture has been discredited, and even Hawking has acknowledged some of its short comings.

Where does that leave us with a finite Tipler cylinder time machine? In limbo! There is no widely accepted proof that a finite Tipler cylinder spinning at any rate would be capable of time travel. There is also another problem. We lack any experimental evidence of a spinning Tipler cylinder influencing time.

Source: How to Time Travel (2013), Louis A. Del Monte